Been happily stuck in a huge Bill Jennings jag lately. Jennings was a phenomenal guitarist active from the '50s to the '70s. He excelled in every style--from bebop to soul to pop to R&B--but the thread that runs through his work is his righteous, greasy tone. A lefty, Jennings played the guitar upside down. If you're not hip to him, you're missing out on being thrilled by one of the great, swinging six-stringers. Check him out!

Bollywood Blues

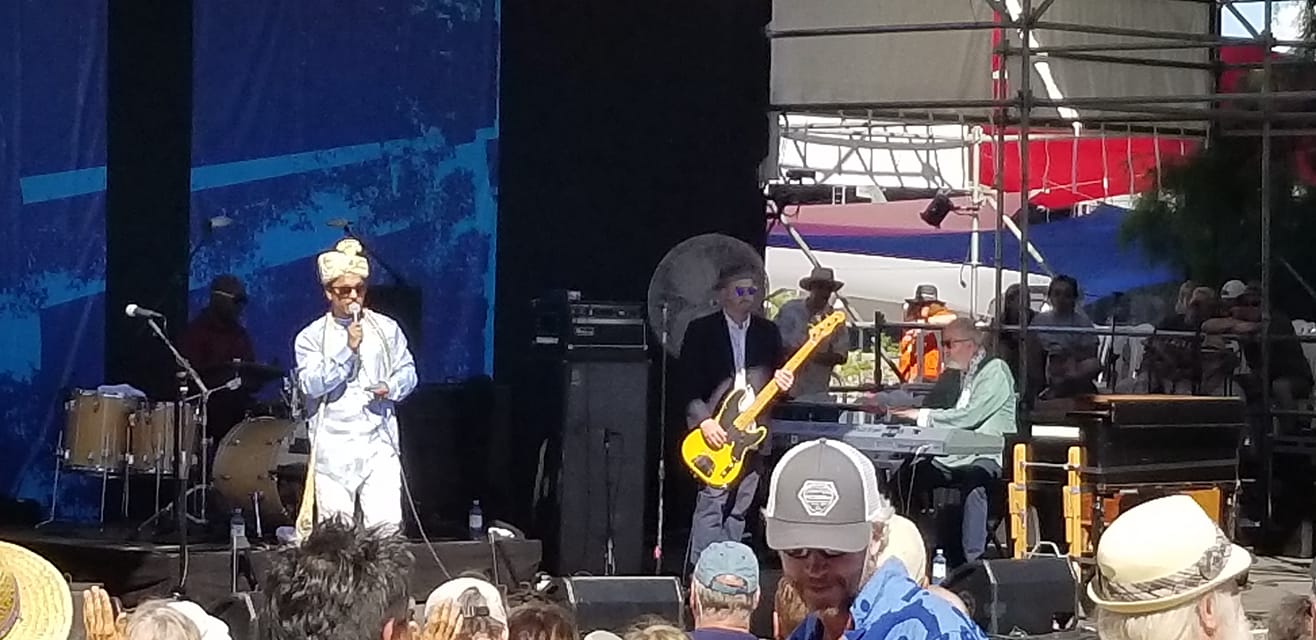

Had a great time playing and being a fan at last week's Waterfront Blues Festival. Kudos to Peter Damman for corralling another stellar collection of topflight acts, and thanks to Bill Rhoades for inviting me to be part of his Harmonica Blowoff. A highlight for me was the great set by Mumbai's Maharajah of the Mouth Organ, Aki Kumar, and his killer band. Aki somehow blended Bollywood, the blues, politics, showmanship, and humor ("I got a girl named Linda Lou, I put the lamb in her vindaloo") into a totally entertaining concept. So great to see a talented young artist doing something creative and different. Be sure to pick up a copy of his great new record, "Hindi Man Blues." Killer stuff!

July Shows

Really looking forward to being part of some great shows in July.

On Wednesday, July 4th, between 8 and 10 pm, I'll be joining fellow harp players Bill Rhoades, Hank Shreve, and Mike Moothart for Bill's annual Harmonica Blow-Off at the fantastic Waterfront Blues Festival in Portland. (Check out Hank's set with his big band at 1 pm the same day.)

On Sunday, July 22, at 12:30 pm, I'll be part of "Riding With The King," a tribute to B.B. King, at the Winthrop Rhythm & Blues Festival. I haven't played Winthrop in a few years and am excited about being back this year. This tribute also features fellow front men Mark DuFresne and John Hogkin, a truly killer band including Tim Sherman channeling B.B. like no on else, David Hudson and GHuy Quintino, and a great horn section.

The following Saturday, July 28th, I'll be joining my legendary band the Mighty Titans of Tone--Brady Daniel Kish, Tim Sherman, Bob Knetzger, and David Hudson--at the great Jazz in the Valley festival in Ellensburg, Washington. We're adding the phenomenal guitarist Al Kaatz for this show. The Mighty Titans and I will be playing an hour-long set at 3 pm in the Rotary Pavilion, and a longer show that same evening (8 pm-11 pm).

Hope to see you at one of these great showcases in July. Support live music this summer!

Matt "Guitar" Murphy

RIP Matt Murphy. Saw him many times in the '70s when he was with James Cotton. I opened for those guys once in Belllingham and had a nice long chat with Matt in the dressing room. We got around to the topic of harp players and I figured that Matt, with his jazz chops and sensibilities, would be a big Little Walter fan. "Walter was great," he said, "but Sonny Boy could get stuff out of the harp that nobody else could." The records Matt did with Memphis Slim are really choice. A wonderful player.

Happy birthday to Isaac Scott, a Big Time Bluesman if there ever was one.

Isaac owned the Seattle blues scene for several decades. He didn’t like to travel and he never had the management to acquire an international reputation, but he certainly had all the musical prerequisites necessary to make it big. Isaac taught himself piano and the guitar as a boy and by the time he was in his early twenties he was touring with the Five Blind Boys of Mississippi. He left that experience as the owner of a surpassingly gorgeous, church-infused voice. It was passion for the guitar playing of Albert Collins that drew him closer and closer to the blues. Collins was based in California in the 1970s and played Seattle often, and he and Isaac became thick as thieves. Isaac adopted Collins’ technique of relying solely on an insanely heavy thumb—no picks or other digits for those two guys. Isaac was always searching for new sounds, so he related to Jimi Hendrix right away. At any rate, Isaac’s gospel vocal style and his rocket-propelled approach to the guitar made him an absolutely unique kind of blues musician.

I met Isaac through drummer Twist Turner, who was playing with Scott at the time, in 1975 and joined his band for the next couple of years. In those days were only two clubs in Seattle that regularly booked blues bands—the Boulder Lounge on First Avenue, and the Place Pigalle (“Pig Alley”) right around the corner in the back of the Pike Place Market. Pig Alley was a classic waterfront dive favored by an eclectic clientele that included local degenerates, sailors on shore leave, aging beatniks, and young hipsters. Isaac had the house gig there. The Boulder was much more upscale with its padded black-and-red leather booths and go-go dancers in cages. Tom McFarland had the regular slot there.

Most of my memories of playing with Isaac revolve around Pig Alley. Isaac would often indulge himself in endless shuffles or slow blues workouts with acres of guitar solos. Isaac had copped Albert Collins’ 60-foot-guitar-cord trick and would often stroll through the club while he was playing. The Pig had a phone booth at the end of the bar, and Isaac would squeeze himself in there with his guitar (no small feat, as Isaac weighed about 300 pounds in those days). Once inside the booth, he would snap the door shut with his elbow and the light inside the booth would pop on, bathing him in a heavenly light from above.

Isaac was a very sweet guy by nature, but he could get hard core when the situation called for it. Once some young hippie “promoters” booked us on a Tuesday night at a local bar for surprisingly big money. Such surprisingly big money that we all grilled Isaac about whether this was a real gig or not. He assured us that he had made a solid deal. We played the entire night for about four people and the promoters didn’t show up until closing time at 1 a.m. They approached Isaac and asked him to step outside for a consultation. This didn’t look promising, and we watched through the windows as the two hippies huddled with Isaac on the sidewalk. Isaac listened to each man in turn as they obviously pleaded with him, gesturing nervously all the while. Isaac’s face became more solemn by the second, finally settling into a frightening scowl as he began to shake his head: "No, no, no…” One of the booking agents made what would prove be a final attempt to placate the big man; it was cut short by Isaac’s big right hand making contact with the side of his head. This initial victim instantly took the form of a crumpled heap on the sidewalk. Isaac turned toward the other promoter, who, in a desperate surge of adrenalin driven by fear of impending doom, bolted up Second Avenue. We all piled out onto the sidewalk just in time to watch Isaac, in a grisly, big-city version of a cheetah running down a defenseless gazelle on "Wild Kingdom," take off at an incredible velocity for a man of his size and make quick work of his second prey. But Isaac wasn’t done yet. He grabbed a hand truck out of the van, rolled it into the bar and proceeded to unplug the club’s expensive new jukebox from the wall, heave it onto the hand truck, and head for the door. He was stopped by the bar owner, and we got our money. Now THAT’S how a real band leader does it, people!

There were other memorable nights (like the time when Albert Collins pulled a knife on Isaac in the back room at a Pioneer Square club) and better venues (like a memorable opening slot at the San Francisco Blues Festival in Golden Gate Park), and I always enjoyed not only playing with Isaac but just being around him. He loved to play and he liked to have a good time. Unfortunately, even when I was in the band he was beginning to suffer from health issues that would take him from us far too early at the very young age of 56.

Isaac was justly famous for his six-string pyrotechnics, but my favorite recording of his is his brilliant and reworking of the Beatles’ tune “Help,” which I never get tired of because it shows off Isaac’s skill, his soulfulness, and his creativity. He probably had more musicality in his little finger than any other talent I’ve ever worked with. RIP, Isaac. None of us have forgotten.

Professor Longhair

There aren’t many things more enjoyable (or more rare) than stumbling on a music or a musician when you are in no way prepared for it—when you have no context or frame of reference for it--and having it or them carry you away.

When I was a college student in New York City in the ‘70s a club on the East Side of Manhattan sponsored a month-long blues piano festival. Each weekend a different lion of the blues piano was featured. At the first installment, I was able to sit ten feet from Little Brother Montgomery (an unassuming, pleasant looking guy who began his career playing in the turpentine camps and whorehouses of Louisiana and who made his first records in 1930) as he played his signature song, “Vicksburg Blues,” the tune of which later became “44 Blues” for Howlin’ Wolf. A week later I was there for a rollicking 90-minute set by the legendary Roosevelt Sykes, the Original Honeydripper, who was just as animated as Montgomery was shy. Sykes was a born entertainer, a monster on the piano, and a great singer who turned and faced and mugged for the audience when he played, a cigar jammed defiantly into the side of his mouth.

On the last weekend of the festival the headliner was a performer with a strange name who I had never heard of or listened to. I never thought about skipping that finale, as the rest of the festival had been so phenomenal, but I didn’t both to prepare for it by checking that unfamiliar player out.

When I got to the club the band was finishing setting up. It was an unusual trio—a Fender bass player, a conga player, and the featured piano player. He was a rail-thin man clad in denim who sported a large, gold front tooth, sunglasses, and longish hair capped by a wide-brimmed hat. I was just finishing my first drink when the group kicked into their show.

This was no blues trio. And this was no blues piano player, although there was a lot of that in there. These three guys were filling the room with some kind of unreal blend of New Orleans r&b, tango, barrelhouse blues, rhumba, and calypso. Whatever it was, I had never heard anything like it, and it was as exciting and funky as hell. After a few minutes of keyboard wizardry, the piano player leaned forward into the microphone and started whistling a slippery horn riff. Then he started singing about a some “big chief” in a wild, croaky kind of voice. Whoever this guy was, he was a trip and half!

This was the great Professor Longhair, aka Roy Byrd, from New Orleans, who once explained his approach this way: “You notice I never play anything straight. Anything I do I put a little pep in it, a little bounce—something to make you know that it’s not a love song.”

Professor Longhair would have turned 100 this year. This week I got a copy of “Fess Up,” a new booklet and DVD that celebrates the awesome uniqueness, talent, and wisdom of Professor Longhair. The context is a concert scheduled in 1980 in New Orleans that would feature three legendary piano players from that city: the elder statesman, Tuts Washington, his protégé, Professor Longhair, and Longhair’s student, Allen Toussaint. The concert never happened—Longhair died in his sleep two days before the show. But the promoters had the good sense to film the three pianists rehearsing for the show, which was later released as a television special called “Piano Players Rarely Ever Play Together.” We learn a lot about each of the men in the film and get to observe the fascinating process by which they work together to figure out how to blend their different styles into a coherent musical program.

“Fess Up” includes a complete version of this film as well as a second DVD containing a 90-minute interview with Professor Longhair, clips of which were used in “Piano Players.” Longhair, who proves to be a savvy character and a humble person (“Those people who play sheet music, they think our stuff is crap”) who nonetheless understood how unique his music was, describes his musical beginnings, the music scene and the music business in postwar New Orleans, his brief period of retirement, and his eventual rediscovery and comeback. “Fess Up,” which comes in a handsome hard-cover booklet full of intriguing photographs and reminiscences of Longhair, is a fitting tribute to one of the great, had-to-be-seen-to-be-believed giants of American music.

Jimmie Vaughan

Happy birthday to Jimmie Vaughan. I had the great good fortune to move to Austin in 1977, just in time to drop into the middle of the blues community centered around the original Antone’s club on Sixth Street. Jimmie was the inspirational force who drew many great blues players to that remarkable scene.

Jimmie was in his mid-twenties but had already been a Texas guitar legend for nearly a decade. After seeing Muddy Waters at a Dallas club in 1968, Jimmie had an epiphany that the blues was his natural home, and ever since he has relentlessly pursued the best aspects of the blues—space, tone, playing behind the beat, and telling a story. The original T-Birds were a quartet, and Jimmie mesmerized audiences and fellow musicians with his ability to play rhythm and lead simultaneously. Blues legends like Buddy Guy and rock stars like Billy Gibbons and Eric Clapton thought of him as a peer.

When I met Jimmie and Kim Wilson in the late ‘70s, I was just as impressed with their attitude as I was with their heavy chops. I knew other white bluesmen with unique talents, but they tended to buy into the entire blues lifestyle and the professional limitations that came with it. Kim and Jimmie were absolutely convinced that the way to become rich and famous rock stars was to only play the real blues shit. And then they proceeded to demonstrate that their preposterous notion was dead right.

After quitting the T-Birds and taking a few years off in the ‘90s, Jimmie re-emerged with a very different approach. He fronted his Tilt-A-Whirl band as the singer, added a rhythm guitarist, and carved his guitar style down even further to lean hard on the soulful, elemental basics that make the blues so irresistible.

Jimmie is still out there playing the real Texas blues and adding new aspects to his mastery. Most recently he’s been working a lot with an organ trio. Whatever he does, Jimmie’s less-is-more approach is always nothing less than the real deal. He’s a national treasure. Every time I listen to Jimmie I remember why I fell so hard for the blues so many years ago.

Raping the anthem

ike almost all my fellow players, I make it a point to never criticize other musicians in public. What would be the point? What kind of performance, no matter how dismal, would ever warrant it?

Now I know.

I didn't catch last night's NBA all-star game, but, after reading some of the backlash about Fergie's rendition of the national anthem, I caught it tonight on YouTube.

There is no existing statute that covers a rape of The Star Spangled Banner. We might want to reconsider that after last night, but the reality is that Fergie won't do jail time for her musical mugging of Francis Scott Key.

I have no problem with singers taking creative liberties with the national anthem. One of my favorite performances of that old British alehouse melody is Marvin Gaye's gorgeous, totally untraditional version at the 1983 NBA all star game.

We Americans are suffering through a grim period in which too many of us are confusing the United States and patriotism with ourselves instead of celebrating that the country belongs to all of us. Last night Fergie took the national anthem to an utterly personal place. Unfortunately, that place turned out to be not an artist's stage but a seamy karaoke-bar platform under the cheap lights where, at five minutes before closing, a would-be chanteuse with eight tequila shooters under her belt desperately tries to score points with the last guy left at the bar.

Fergie doesn't deserve condemnation for being a cosmically godawful singer. She's not the first vocalist to try to go to soul town without knowing what that even means, much less how to get there. And it's not a crime that the national anthem clearly means absolutely nothing to her personally. What earns her our lasting scorn is that she had no clue that the bar song she was sleazing her way through (she did every low trick short of simulating oral sex with the mic) was a song that actually meant something to everybody else in the room. This profoundly disturbed woman needs to go away somewhere for a few years and give the country enough time away from her to drive all memory of last night's assault from our collective consciousness.

Steve Ramsey

Just learned that Steve Ramsey has done his last gig on earth. I had the amazing good fortune of being in a band with Steve when I lived in Massachusetts and of becoming one of his many friends. Steve was a great guy with a fabulous smile and a sardonic wit. Steve played with many of the best in the business because he was a musician's drummer--one of those rare people who could tell a real story behind the kit. Very sad, tough news, but it helps to recall the many great times with Steve.

Where no one stands alone

Like many other performers, Merle Haggard knew loneliness. In fact, he made the decision to dedicate his life to music as Prisoner 845200 in San Quentin prison, during a stay in solitary confinement with only pajama bottoms, a blanket, a stone floor, and a Bible. This is a surpassingly soulful rendition of a gospel classic that Haggard included in a religious album he recorded in memory of his mother in 1981.

BluesHarmonica.com

On a recent trip to the Bay Area, I had the pleasure of finally meeting David Barrett, a great harmonica player who is the genius behind BluesHarmonica.com, a phenomenal resource for players of the world's finest instrument. Had the honor of sitting down with David for a filmed discussion about the harp. Tons of fun. Here's a snippet that David posted to YouTube today.

Miller and Sasser

Every city has its musical gems—performers and bands who are the favorites of the musician community and passionately devoted, in-the-know listeners and fans. Groups who could attract a national audience but in the meantime can still be experienced up close and personal in local clubs. I recently moved to Portland, and one of the Rose City’s true musical jewels is that town’s premier alt-country act, Miller and Sasser. The group has just released its second CD, “Tell It To The Jukebox,” and it’s an effort that fully displays all the unique hallmarks of this great band: Matthew James Sasser's gorgeous voice, Chris G Miller’s world-class guitar chops (he’s a member of the Oregon Music Hall of Fame and is the guy who Dave Alvin, Asleep At The Wheel, and Marcia Ball call when they need a guitar player), the stellar songwriting of both front men (heavily influenced by the hook-laden country hits of the ‘70s and their jazz and r&b backgrounds), and the ear-opening twin-guitar voicings of brothers Chris and Ian Miller. “Tell It To The Jukebox” manages to be just as fulfilling and exciting as the group’s live shows, which is really saying something. If you’re not hip to these guys, or if it’s been a while, please go see them at one of their local shows (see their calendar at millerandsasser.com) and get yourself a copy of “Tell It To The Jukebox” from CDBaby and other outlets. Miller and Sasser—my hot musical tip of 2017. They're killing it.

Howard Carroll

Yesterday we lost Howard Carroll, the phenomenal singer and guitarist in the legendary gospel group the Dixie Hummingbirds. He was 94. Carroll joined the Birds in 1952 and quickly set the standard for the electric guitar in a gospel setting. Carroll grew up on the blues, country and bluegrass, and the jazz stylings of Charlie Christian. The only instrumentalist in the Birds, Carroll's unique genius was his always-perfect use of the guitar to complement the group's gorgeous voices. A truly masterful musician.

George Jones

Best birthday wishes to George Jones, the most searing country music heart singer ever. Jones was a product of the Big Thicket in southeast Texas, a rough landscape that harbored even wilder inhabitants. George's father would regularly come home drunk and violent late at night and wake the entire family up, demanding that the kids sing to him, so George had a problematic relationship with music from the beginning. He wrestled multiple personal demons throughout his life, but he never lost his impossibly elastic, multi-octave voice, which year after year produced some of the most nakedly emotional performances in recorded music.

The Blue Yodeler

Happy birthday to the father of country music, Jimmie Rodgers. Rodgers was a tubercular 29-year-old former railroad man when he showed up in Bristol, Tennessee in 1930 to audition with his backing group for RCA Victor's Ralph Peer. The band was cleared for a recording session, but the group broke up the night before and Rodgers ended up recording two solo sentimental numbers. They sold well enough to earn Rodgers a second session, at which he recorded the first of his famous "blue yodels"--"T For Texas"--which catapulted Rodgers to stardom. When record sales evaporated during the Depression, Rodgers' popularity kept RCA Victor from bankruptcy. Rodgers' recording career lasted only six years (he died of tuberculosis at the age of 35), but he established the blend of sentimental tunes and blues numbers that was the pattern for country music for decades, and he left us with many remarkable recordings--including "Blue Yodel #9," an early interracial session with Louis Armstrong and his wife, Lil Hardin Armstrong.

Johnny Hodges

Happy birthday to the one and only Johnny Hodges, the owner of that patented, impossibly gorgeous alto sax tone. Here he is weaving a silky path through the melody of Billy Strayhorn's "Passion Flower."

Fifty Cents and a Box Top

Just finished reading "50 Cents And A Box Top," the new memoir by legendary harmonica ace Charlie McCoy. Charlie recounts his amazing personal journey from young blues freak and rockabilly singer to a completely unique harmonica stylist to one of the most in-demand session players in the history of popular music to best-selling recording artist to international music star to member of the Country Music Hall of Fame. What a ride! My favorite chapters were the ones about the thousands of sessions Charlie did behind folks like Brenda Lee, Loretta Lynn, Bob Dylan, and Paul Simon. (There's a jaw-dropping anecdote about a Leonard Cohen session that confirmed all my personal suspicions about that artist.) Harmonica players will especially appreciate the appendix with complete details of the harmonica model, key, and, in some cases, special tunings that Charlie used on his own stunning instrumental recordings. Charlie is one of the great musical geniuses of our time and one of the nicest guys in the business. If you have any interest in music, you will love this book.

Austin

When I lived in Austin back in the day, it seemed like the blues capitol of the world. It's still pretty heavy, decades later. Over the past two days I have been entertained by Kim Wilson, Rick Estrin, Jimmie Vaughan, Bob Corritore, Annie Raines, Sue Foley, Angela Strehli, Lou Ann Barton, Bob Margolin, Mud Morganfield, Lazy Lester, Marcia Ball, Emily Gimble, Derek O'Brien, Sarah Brown, Johnny Moeller, Jay Moeller, Kyle Rowland, and Mike Keller, among others. That's in just two days! This afternoon I guested at a really fun recording session with Kathy Murray, Bill Jones, and keyboard wizard Floyd Domino. Tonight it's back to Antone's for the great Barbara Lynn, and tomorrow I'll be at a table near the stage for the fabulous Paul Oscher's regular weekly gig at C-Boys. Whew!

30th annual waterfront blues festival

Thrilled to be part of the 30th annual Waterfront Blues Festival this July 4th in my new home of Portland. I'll be playing and singing in Bill Rhoades' 16th Annual Harmonica Blowoff, along with heavy harpers Mark DuFresne, Hank Shreve, Mike Moothart, and Mr. Rhoades himself. Many thanks to Bill and Peter Dammann for the opportunity. We play just before the huge fireworks spectacular, which is only appropriate. Excited about seeing many great shows at the West Coast's premier blues festival, including the Paul deLay tribute and the return of the always amazing Curtis Salgado.

The Howlin' Wolf

Today is the birthday of Chester Burnett, the Howlin’ Wolf.

I was privileged to catch the Wolf many times. The Wolf had one of the most unique and amazing voices in all of music, but he was also an outstanding harmonica player. When I was twenty I saw the Wolf do a show on a Tuesday night at Sir Morgan’s Cove in Worcester, Massachusetts. It was a slim crowd, but the Wolf was in bigtime harmonica mode, blowing some incredible stuff. Impossibly huge tone.

Paul Oscher, Muddy Waters' former harmonica player, had introduced me to tongue blocking on the harp a couple of months before, so I had that concept on the brain. Wolf’s first set ended and the rest of the band hit the bar, but the Wolf stayed on his stool under the lights, staring at the floor. Naturally, I just had to ask him whether he tongue blocked on the harp.

As I walked toward him my legs got wobbly. The Wolf was one of the largest—and certainly most intimidating—humans I had ever approached. Somehow I managed to open my mouth and stammer out an introduction. I was a harp player, I explained. I threw out Paul’s name, haltingly explained that he had just introduced me to this mysterious technique, complimented the Wolf effusively on his harmonica work, and asked him if he tongue blocked on that thing.

An eternity passed as the Wolf slowly lifted his penetrating gaze from my shoes to my eyes. Several seconds of silence ensued, which felt like forever. Then suddenly that otherworldly voice was addressed to me.

“The Wolf don’t tell nobody his tricks,” the Wolf balefully intoned. “If you find out, the Wolf don’t mind. But the Wolf ain’t gonna tell you about it.” I beat a hasty retreat.

One thing for sure: there will never be another Howlin' Wolf.

![Isaac_Scott_at_SF_Blues_Fest[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52bc96d8e4b089a76bb4aefa/1529096819573-C35AFCMVE36O0UNI2OA2/Isaac_Scott_at_SF_Blues_Fest%5B1%5D.jpg)