On May 24, 1951, a twenty-year-old outfielder for the Minneapolis Millers in the American Association, was sitting in a movie theater in Sioux City, Iowa, when this message flashed across the screen: WILLIE MAYS CALL YOUR HOTEL.

When he got back to his room, there was another message waiting for him—to call Leo Durocher, the impatient, profane manager of the New York Giants. When the two were finally connected via phone, Durocher told Mays that he was calling him up to the majors to help the Giants, who were struggling.

Mays protested, saying that he wasn’t ready for the majors. After all, he had only played 35 games in Triple A.

“What are you hitting, Willie?”, asked Durocher.

“.477,” replied Mays.

Durocher told him in no uncertain terms to get his ass to Philadelphia, because the he was starting in center field for the Giants the very next day.

The Giants won all three games against the Phillies. Mays went 0-for-5 that first game and 0-for-12 for the three-game series against the Phillies.

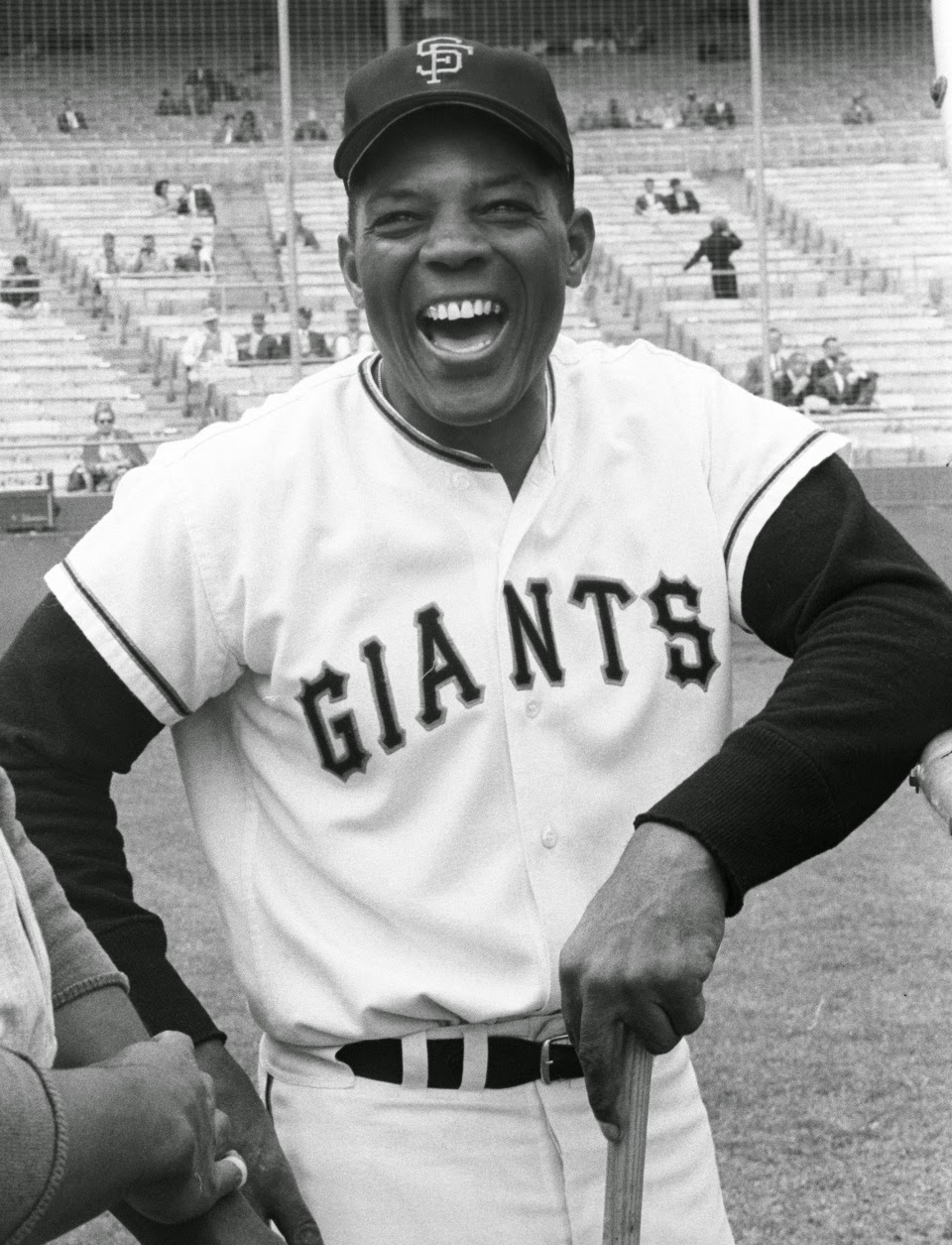

Twenty-year-old Willie Mays meets the press before his first big-league game

Willie was shaken by his debut slump at the plate, but Durocher sat him down.

“Look son,” Durocher told him. “I brought you up here to do one thing. That’s to play center field. You’re the best center fielder I’ve ever seen. As long as I’m here, you’re going to play center field. Tomorrow, next week, next month. As long as Leo Durocher is manager of this team you will be on this club because you’re the best ball player I have ever seen.”

The next day the Giants returned home to the Polo Grounds in New York to face the Boston Braves and their star pitcher Warren Spahn, the winningiest lefty in baseball.

In the first inning Spahn dispatched Eddie Stanky and Whitey Lockman. Mays took his place in the batter’s box and knocked a Spahn pitch over the left-field roof for his first major-league hit. He was on his way. ("I'll never forgive myself,” Spahn joked years later. “We might have gotten rid of Willie forever if I'd only struck him out.")

Willie Howard Mays, Jr. was born in Westfield, Alabama in 1931. His grandfather was a talented baseball player, his father played semi-pro baseball in the Negro Leagues, and his mother was locally famous for her skills in basketball and track.

In high school, Mays was a star point guard, quarterback, and outfielder and played in the Negro Leagues on weekends. He helped the Birmingham Black Barons win the Negro League World Series in 1948 and was pursued by several major-league teams. He ended up signing with the New York Giants.

Willie Mays (in the back row, center) with the Birmingham Barons of the Negro League

Willie Mays won the National League Rookie of the Year award in 1951. Mays was in the on-deck circle when Bobby Thompson hit his “Shot Heard Round The World” homer that put the Giants in the Subway Series against the New York Yankees that year. The Giants were beaten 4 games to 2, but the 1951 Series was memorable in that it was the only time Mays played against Joe Dimaggio and because the Giants fielded the first major-league all-African-American outfield—Mays, Hank Thompson, and Monte Irvin.

Mays was drafted into the Army during the Korean War and missed the next two seasons. He came roaring back in 1954 with a spectacular year in which he lead the American League in hitting with a .345 average, hit 41 homers, and was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player. He also led the Giants to another World Series, this time against the Cleveland Indians.

Willie and the Giants swept the Indians in that Series, which is known for one of the most famous defensive plays in baseball history.

In the first game, held in the Polo Grounds in New York, the Giants and the Indians were tied 2-2 in the eighth inning. Giants pitcher Sal “The Barber” Maglie walked lead-off hitter Larry Doby and then Rosen singled to put men on second and third with no outs. Don Liddle was brought in to pitch to the next batter, Vic Wertz, who already had three hits in the game.

To say that center field in the Polo Grounds was as big as the Grand Canyon would be only a slight overstatement. You could hit a ball 482 feet toward the centerfield wall there and still wind up one foot short of a home run. If a centerfielder positioned himself 400 feet (a home run in most parks today) from home plate, the wall would be 83 feet behind him.

Mays was playing in shallow center field when Wertz stroked a screaming shot to straight-away center. Mays instantly turned his back to home plate and streaked to the spot, about 425 feet from home, where the ball was destined to return to earth. Running at full speed, Mays made a spectacular, over-the-shoulder catch with his back to home plate as his hat flew off his head.

Mays’ grab of Wertz’ fly ball has been forever immortalized in sports history as “The Catch,” but the next part of the play—let’s call it “The Throw”—was actually even more impressive. As soon as the ball touched his glove, Mays somehow managed to plan his feet, spin back back towards the plate, and launch a perfect strike to second base, keeping the baserunners from scoring. The Giants got out of the inning and went on to win the game with a walk-off home run from Dusty Rhodes.

“The Catch”

The 1950s were the glory days for New York City’s baseball teams, with the game’s top centerfielders—Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, and Duke Snider—all playing in the city and at the peak of their careers. But in 1958 the Dodger decamped to Los Angeles and the Giants moved to San Francisco. It’s intriguing to think about how many more home runs Mays might have hit had he not played so many games in the wind tunnel by the Bay they called Candlestick Park.

My grandfather took me to my first major-league game in 1961. If I would have designed a perfect game in my mind beforehand, that day in the seats on the third-base side was it. The Giants beat the hated Dodgers in a close game. Mays hit a home run and Juan Marichal won the game. Given the victory, I was gracious enough to acknowleddge the homer hit by Duke Snider in that game, as he was the only Dodger I could stomach at that tender, ultra-partisan age. (Actually, I still feel the same way, although Sandy Koufax eventually joined Duke on my two-person list of Dodgers whom I respect.)

In 1962 the Dodgers and the Giants tied for the NL pennant and the Giants had to win a three-game playoff to advance to the World Series against some team called the New York Yankees, who for some reason were huge favorites. The Giants took New York to seven games, the last of which was played in Yankee Stadium. Bill Terry pitched for the Yanks and Jack Sanford was on the mound for the Giants. The score was 1-0 Yankees when the Giants came up to bat in the ninth. Matty Alou led off with a successful bunt, but Terry struck out Felipe Alou and Chuck Hiller. Willie Mays delivered a clutch, two-out double that should have tied the game, but Roger Maris came up with a great throw from right field that kept Matty Alou from scoring.

As I watched on our living-room television, Terry decided to pitch to Willie McCovey instead of walking and facing the equally fearsome Orlando Cepeda. McCovey crushed Terry’s second pitch—he would later say that it was the hardest he had ever hit a ball—over Terry’s head.

Bobby Richardson was the Yankees’ second baseman. If you stretched Bobby Richardson’s slight frame on a medieval rack for nine months and put lifts in his shoes, you might have extended him to a height of five feet, nine inches. I followed the track of what was sure to be a Series-winning home run off McCovey’s bat for about half a second and then watched Richardson somehow leap about twelve and a half feet in the air and catch the line drive in the uppermost webbing of his glove. It was the darkest day of my young life, and I still hate to think of that obscene moment.

If you are curious as to whether baseball has changed much since those days, just ponder the game between the Milwaukee Braves and the Giants that took place on July 2, 1963. Warren Spahn and Juan Marichal each pitched SIXTEEN scoreless innings in the most epic pitching duel ever. Marichal held Hank Aaron hitless in six at-bats. Spahn took the mound in the sixteenth, after pitching for FOUR HOURS AND TEN MINUTES and gave up a walk-off homer to—you guessed it—Willie Mays.

In the 1965 season Mays rose to the occasion again, hitting 52 home runs, winning his second NL MVP award, and becoming the highest paid player in baseball.

That was Willie’s high-water mark. The financially strapped Giants traded him to the Mets in the middle of the 1972 season, which actually felt right because Willie was always more popular with New York fans than he was with San Franciscans. He hit a home run in his first plate appearance with the Mets. In 1972 and ’73 Willie was the oldest position player in baseball.

As fate would have it, I was going to college in New York City when Mays came to the Mets, and I made two trips out to Shea Stadium to try to catch him. He didn’t play in the first game I went to, but I saw him pinch-hit a single the next time.

In 1973 he became the oldest position player (he was 42) to play in a World Series, but he missed a ring when the Oakland A’s beat the Mets. Willie’s last trip to the plate came in that Series.

Willie Mays played twenty-two seasons in the majors and racked up an unreal legacy:

· Retired with a career batting average of .302, 3,283 hits, 660 home runs (unjuiced), and 7.095 outfield putouts (all-time MLB record).

· Won Rookie of the Year, two MVP awards, and 12 Golden Gloves (an award that didn’t even exist during Mays’ first four seasons).

· HoldsHe holds the MLB record for most All-Star game appearances Most All Star games (24).

· Had eight consecutive 100-RBI seasons.

· Hit four runs in a game. (He was on deck ready to go for a fifth when the game ended.)

· Is the only major league player to have hit a home run in every inning from the 1st through the 16th innings.

· Elected to the Hall of Fame in 1979. Twenty-three sportswriters voted AGAINST him. New York Daily News columnist Dick Young wrote, "If Jesus Christ were to show up with his old baseball glove, some guys wouldn't vote for him. He dropped the cross three times, didn't he?"

The fans and players who saw him in action knew where Willie Mays stood in the history of baseball.

Leo Durocher talked about the obvious joy that Willie had for the game as well as his ridiculous talents: “If somebody came up and hit .450, stole 100 bases, and performed a miracle in the field every day, I'd still look you right in the eye and tell you that Willie was better. He could do the five things you have to do to be a superstar: hit, hit with power, run, throw and field. And he had the other magic ingredient that turns a superstar into a super Superstar. Charisma.”

Ted Williams, who hardly every talked, much less doled out compliments to other players, put it best: “They invented the game for Willie Mays.”

In July of 2009 President Barack Obama flew Air Force One to St. Louis to throw out the first pitch at the All Star game. He invited Willie Mays to accompany him, and the two black pioneers had a extraordinary discussion during the flight, with Mays telling the first black President that he was so proud on Electiion Night 2008 that he couldn’t sleep.

Obama awarded Willie Mays the Medal of Freedom in November, 2015. "Willie also served our country,” Obama noted at the ceremony. “In his quiet example while excelling on one of America's biggest stages he helped carry forward the banner of civil rights. It's because of giants like Willie that someone like me could even think about running for president.”

The “Say Hey Kid” turns 88 today.