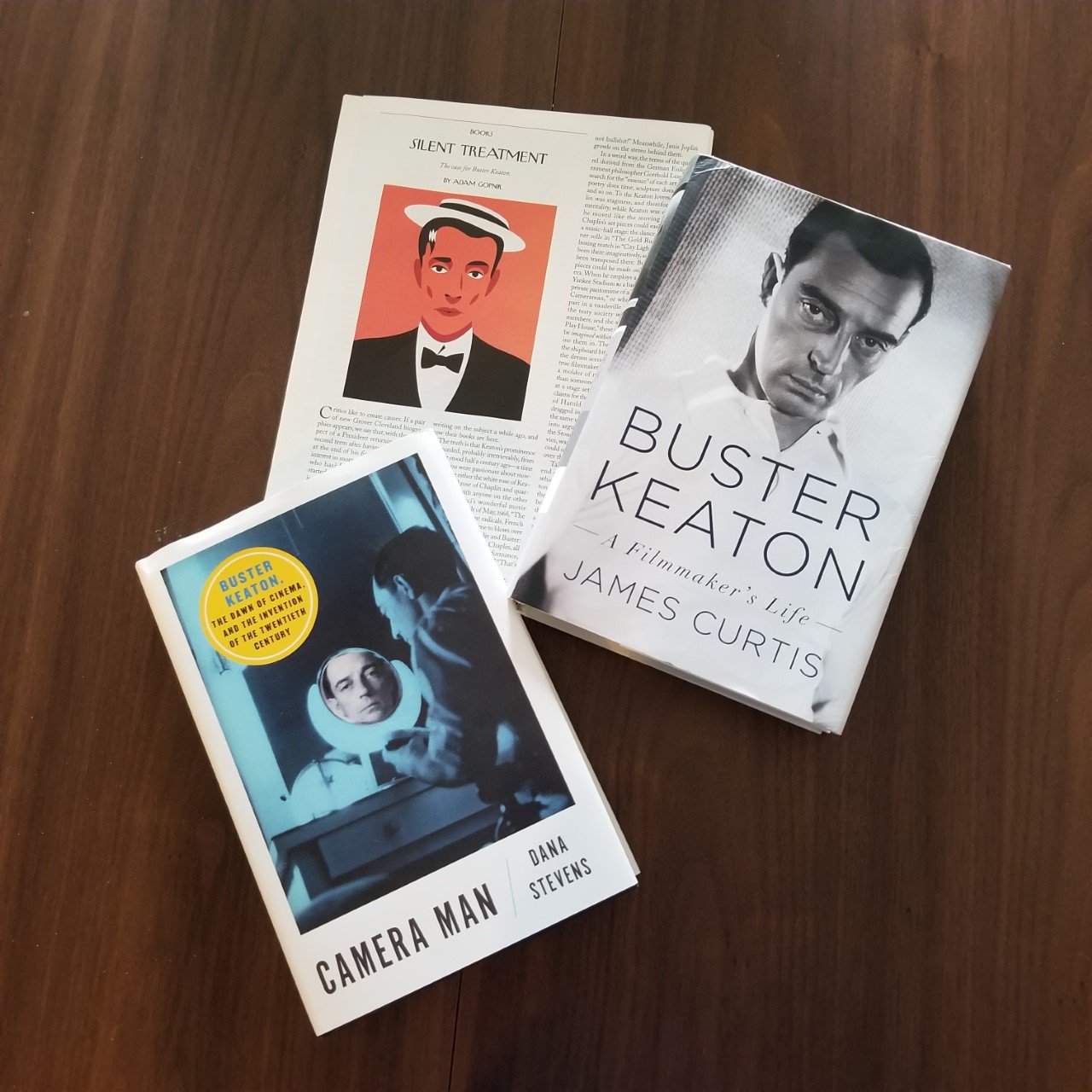

Buster Keaton is like a comet that re-enters the Earth’s orbit every fifty years. He became international film star and director in the 1920s. In the 1970s, there was a Keaton revival that had critics arguing with each other about whether Keaton or Charlie Chaplin was the more brilliant filmmaker. Another half a century has now passed since those spirited debates, and Keaton suddenly seems to be everywhere again: a lengthy profile by Adam Gopnik in The New Yorker, not one but two new biographies, and a biopic of Buster in the works.

I first experienced Keaton during the second of his semicentennial resurrections, thanks to a screening of Steamboat Bill Jr. in a college film-studies class taught by Andrew Sarris, who was then the film critic for the Village Voice. Seeing Keaton’s 1928 classic was a revelation to me. It had been made in the movies’ relative infancy. It was a black-and-white film. It was silent. But it beat just about anything this movie junkie had ever seen in terms of comic acting, physical stunts, and cinematography.

Most startling of all to this neophyte was Keaton’s physical presence onscreen and how the movie was built around it. His sharply beautiful, axe-blade profile gave him the look of an arrowhead, which was perfect because that’s what he portrayed in his films—a human projectile. In Buster’s films, the arrow—in the form of a quest or labor—is launched in the first few minutes. He has to find a wife within seven days or he will lose his inheritance. He has to recapture a military locomotive. He has to make his long-lost father proud of him. He has to put together a pre-fabricated house. He has to find some stolen diamonds. The rest of the film is Keaton relentlessly hurling himself forward, against all obstacles, in pursuit of his goal.

The quest is transformative. Buster’s character is often introduced as an effete miltquetoast, but once launched by the bow of the premise, he is transformed into a stonefaced and determined man on a mission, a brilliant strategist, a master of engineering and physics, and a phenomenally gifted athlete. This metamorphosis feels genuine because it is—those are the qualities that defined the Joseph Frank Keaton, the real man.

Keaton’s parents were vaudevillians, and Buster was part of the act by the time he was a year old. The toddler Buster was funny because he was dressed and made up as a miniature replica of his father’s onstage character. By the time he grew into boyhood, Buster’s prodigious skills as an acrobat and a comedian were obvious to all, and Keaton’s father remade the act around his son. Buster became a mute, recalcitrant child who refuses to obey his father. Father attempts to discipline his child, all hell breaks loose, and the patriarch begins to literally hurl his son the full length of the stage into the scenery, the frightening velocity and distance of the toss due to a wooden handle Buster’s mother had sewn into the back of his stage outfit. (Buster was billed as “The Human Mop.”) Within a few years, Buster’s character was fighting back against parental tyranny. Audiences never forgot watching Buster’s father shaving himself in front of the footlights with a straight razor while, behind his back, his son is swinging a basketball tied to a string in ever-expanding circles, the leather orb inching closer and closer to the back of his father’s head with each revolution.

By the time Buster Keaton was a teenager, his father had begun to drink before shows and the stage act had begun to reflect a real-life conflict between the two. In 1917, nineteen-year-old Buster quit the act and went to New York to start a new vaudeville career as a solo performer. One afternoon a chance encounter with a friend on the street led to Keaton visiting a movie studio on West 48th Street where comedian Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle was shooting one of the comedy shorts that had made him a national sensation. Keaton had a lifelong fascination with anything mechanical, and after the day’s shooting was over, he asked Arbuckle to explain the movie-making process by taking a camera apart and explaining how film was developed, cut, and spliced together.

Keaton was hooked, and he took a huge pay cut to quit Broadway and join Arbuckle’s team. A few months, later, when Roscoe graduated to making feature films, Keaton was given Arbuckle’s studio (which had been relocated to Los Angeles) and was signed by producer Joseph Schenk to produce a series of his own comedy shorts.

Keaton became one of the greatest, if not the greatest, of the early filmmakers because he respected his medium and his audience, because he immediately grasped its endless possibilities, and because he brought a spectacularly visual vision to it.

As he began to direct his own films, Keaton considered a comment Arbuckle had once made to him. “You must never forget,” Arbuckle had told him, “that the average mentality of a movie audience is twelve years.”

“I thought about that for a very long time,” said Keaton later. “For three months, in fact. Then I said to Roscoe, ‘I think you’d better forget the idea that the movie audience has a twelve-year-old mind. Anyone who believes that won’t be in pictures very long, in my opinion.’ I pointed out how rapidly pictures were improving technically. The studios were also offering better stories all the time, using superior equipment, getting more intelligent directors…’Every time anyone makes a good picture,’ I said, ‘people with adult minds will come to see it.”

Where others saw film as a new kind of theater experience or new kinds of manufactured sets, Keaton saw it as a door into the whole, real world. “On the stage,” Keaton once told an interviewer, “even one as immense as the New York Hippodrome stage, one could only show so much. The camera had no such limitations. The whole world was its stage. If you wanted cities, deserts, the Atlantic Ocean, Persia, or the Rocky Mountains for your scenery and background, you merely took your camera to them. In the theater you had to create an illusion of being on a ship, a railroad train, or an airplane. The camera allowed you to show your audience the real thing: real trains, horses and wagons, snowstorms, floods. Nothing you could stand on, feel, or see was beyond the range of the camera.”

“Keaton lived in the camera,” said Arbuckle. Buster’s comedy was visual, images captured via long shots—no cheating cross-cuts or closeups for Keaton. The Playhouse, Keaton’s 1921 cinematic valentine vaudeville, just one extended visual gag. Buster is literally the entire show—the conductor and all the musicians in the pit band, the people in the audience, the stagehands, a dance team, even—in one of the most hilarious feats of animal mimicry ever filmed—a rogue chimpanzee. But the sequence that kept Keaton’s fellow movie professionals coming back again and again to see The Playhouse was one in which nine different Busters line up across the screen and perform a unison dance number in a minstrel show Nothing like it had ever been filmed. As one historian has explained, Keaton accomplished this startling scene by building “a light-proof box for the camera, its front comprised of nine equally spaced shutters that could be closed independently of one another, allowing for the exposure of nine different vertical slivers of the frame.” In 1921, all film cameras were hand-cranked, so to make Keaton’s illusion work, the cameraman had to hand crank a take featuring one of the nine Keatons, rewind the film back to the starting point, and film the next Keaton minstrel while cranking the camera at exactly the same speed—and do this nine times.

After starring in and directing eleven brilliant comedy shorts, Metro signed Keaton to develop his own feature films. Over the next five years, Keaton—serving as producer, star, scene planner, chief gag writer, and director—released eleven outstanding features in one of the great sustained periods of high-level creativity in the history of popular entertainment. Five of them—“Sherlock Jr.,” “The Navigator,” “The General,” “Steamboat Bill Jr.,” and “The Cameraman”—have been included in the National Film Registry, making Keaton one of the most honored filmmakers on that prestigious list.

In 1928, Keaton lost creative control of his films and became a victim of the new formulaic Hollywood studio system. He began to drink heavily. His marriage failed. Silent films were replaced by the talkies. 1932 found Buster reduced to playing second banana to Jimmy Durante in a pair of films. Three years later, Keaton was a patient in the psychopathic ward of the National Military Home in Los Angeles.

In 1940, Keaton married Eleanor Norris, a beautiful MGM contract dancer who was 23 years his junior. They remained together the rest of his life, and by all accounts Norris was the best thing that ever happened to him. Buster limited his drinking to an occasional beer and kept working. He directed and starred in a series of shorts for the small Educational Pictures company. He got back on MGM’s payroll as consultant on comedy films, including pictures by the Marx Brothers and Red Skelton. He started appearing in bit parts in films, including memorable cameos in Sunset Boulevard and Charlie Chaplin’s Limelight. He had a successful run in Paris as the star of the Cirque Medrano.

In 1948 Keaton visited his son Jim, whose home featured one of the first television sets. Keaton stared at the ten-inch screen, transfixed, for several hours. “That,” he told his son, “is the future of entertainment.” Keaton jumped into the new medium with both feet in the 1950s. He starred in his own series, The Buster Keaton Show, sponsored by Studebaker, and appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show several times.

As Buster launched a new career on the small screen, prominent film critics Walter Kerr and James Agee published essays lauding Keaton’s silent features and making the case that Keaton belonged among the very best American film directors. Many of Keaton’s films were presumed lost until 1956, when actor James Mason, who had bought the mansion Keaton had built in the 1920s, discovered a vault in a shed on the property that contained 35mm prints of five Keaton films. An energetic hustler named Raymond Rohauer began amassing a nearly complete collection of Keaton’s shorts and features, cleared up a snarl of copyright issues, and launched a partnership with Keaton to get his films shown again in theaters and museums.

In 1957, Paramount released a Keaton biopic starring Donald O’Connor. The film was a predictable mess, but Keaton used the money he made from it to purchase a rural, ranch-style home in Woodland Hills, California. He stayed busy. The Motion Picture Country House, to which many of the old Hollywood stars had retired, was only ten minutes from Keaton’s home. “I drive by sometimes and talk to some of the old timers,” Keaton once a reporter, “but it makes me so sad I don’t do it often. They live in the past. I don’t. One Easter Sunder I went to a party at Mary Pickford’s house. Everybody from silent films was there. I tried to have fun, but I discovered we had nothing to talk about. Some of them had never heard a Beatles record. They hadn’t kept up with the times.”

Keaton became a ubiquitous presence thanks to appearances in a slew of television commercials. He toured with dinner theater companies. He popped in several American International teen pictures, including Beach Blanket Bingo and How To Stuff A Wild Bikini, appeared on the television shows Candid Camera, Route 66 and The Twilight Zone, and contributed cameos to the movies It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, Around the World in Eighty Days, and A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum.

The Nobel Prize winning novelist and playwright Samuel Beckett only visited the United States once, in 1965. What brought him to New York was the chance to make his own film (entitled, characteristically, Film) with Buster Keaton. Beckett had tried to recruit Keaton for the role of Lucky in the 1956 Broadway production of Waiting for Godot, but Keaton found the play incomprehensible and turned it down. Keaton was similarly bewildered by Film. “He hated every minute of it,” Eleanor Keaton recalled. “He did exactly what they told him to do and not one whit less or one whit more, because he didn’t know what he was doing.” Director Alan Schneider recalled that Keaton “was totally professional: patient, unperturbable, relaxed, easy to tell something to, helpful.”

If you’re not familiar with Keaton’s films, I recommend watching the short One Week and the feature Steamboat Bill, Jr. The premise of One Week—newlyweds are given a kit home as a gift and have to assemble it themselves—results in a nightmarish, surreal structure that spins like a top in a violent storm and ejects its occupants, and a rousing finale involving the first of Keaton’s many film locomotives. The General is regarded by many as Keaton’s classic, but in my opinion Steamboat Bill Jr. is a better introduction to the full spectrum of his genius. The film benefits from one of Keaton’s best plot lines (an effete man-child struggles to help his rugged, he-man father save his decrepit steamboat business), some of his best acting, and a relentless cavalcade of perfectly executed cinematic moments that range from subtle character revelations to jaw-dropping, what-did-I-just-see impossibilities. I know that this post is dripping with superlatives, but you could make a strong case that Buster Keaton was the greatest stuntman in the history of film, and some of his greatest physical feats and gymnastic pratfalls are immortalized within the frames of “Steamboat Bill Jr.”

James Curtis’ new “Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life is the most thorough and well-researched of the several Keaton biographies that have been published over the years.

Buster Keaton died in 1966. He had lived to see his films play once again to packed houses and standing ovations around the world. The Keaton arrow that had been launched on that Arbuckle movie set in 1917 had reached its target. Dead center. Bullseye.