New York city 1969-1974

The Sting Rays: (left to right) me, Louis X. Erlanger, Bob Ahrens, Jim Becker, and John Brancati

(Photo by Jeff Fereday)

The first band I was in was a group called The Sting Rays. We all met as students at Columbia University in New York City in the '70s. It was an ideal first band for me: the other guys were great people (I'm still in close contact with all of them), funny, much better players and more experienced than I was. Our first gig was a Circle Line boat cruise sponsored by the Columbia sophomore class. The first few dozen ticket buyers got a free tab of mescaline; we were lucky to get back to port. The Sting Rays did an eclectic mix of material with a heavy emphasis on the blues and became a popular dance band on campus.

I had never been east of Wyoming before going off to Manhattan for college, so I got educated in more than just English and comparative literature while I was there. New York was never a huge town for blues, but there was a decent local scene with people like Victoria Spivey, John Hammond Jr., Paul Oscher, Bill Dicey, Sugar Blue, and the Brooklyn Blues Busters.

We used to see Oscher at the Marble Lounge, which had kids’ marbles embedded in the ceiling. Oscher would play harmonica, guitar, and piano—sometimes on the same song. This was a guy who could summon the instrumental sounds of Little Walter, Muddy Waters, and Otis Spann. There was nobody like him. The Brooklyn Blues Busters were a really talented band that featured Howard Levine on guitar, John Nuzzo on harp, Johnny Ace on bass, and, for a time, Fran Christina on drums. They were inspirational to us.

I remember seeing Bill Dicey back up John Hammond Jr. and following him backstage to ask him where he got his biscuit-shaped harmonica microphone, just like the ones in the photos of my Chicago blues harp heroes. He looked at me like I was crazy. “Radio City,” he muttered. He was right. I went downtown to the radio equipment stores that still dominated that part of town and they had hundreds of them for $10 apiece. If I had bought a hundred of them I could have financed my kids’ college tuitions thirty years later. They go for up to $300 now.

Victoria Spivey played the clubs in the Village pretty regularly. She had her own blues record label. Bob Dylan made his recording debut playing harp behind Big Joe Williams on a Spivey album. Victoria Spivey made her first records in the 1920s and was in the first generation of female blues singers. She had honed her act in theaters and night clubs and her presentation was somewhat formal and sophisticated. She brought great people to town. Thanks to her I got to see Lonnie Johnson in person. Johnson was a very sophisticated guitarist and singer with an incredible pedigree (he recorded some stellar guitar-duet sides with jazz legend Eddie Lang) whose forte was very tuneful blues. Danny Russo, my favorite harmonica player on the New York blues scene in those days, also recorded for Spivey’s label. Danny was a very soulful singer, too, and he lived for the blues. He was so talented that he was personally close to Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. Sugar Blue, who was just making a name for himself as a harmonica player, also made his recording debut on a Spivey album.

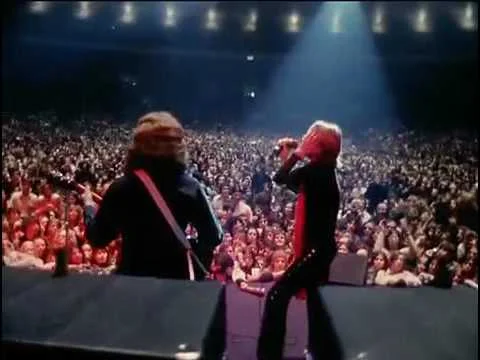

The Rolling Stones at Madison Square Garden, November 1969

Three months after I arrived in New York City the Rolling Stones played Madison Square Garden, and somehow I scored a nosebleed seat for that show. The Beatles had just broken up and the Stones looked to be their heir apparent as the top rock and roll band, but they were somewhat of a mystery for U.S. fans because they hadn’t toured America for three years due to their drug busts. This was the ill-fated tour that culminated in the Altamont fiasco, but it certainly put the Stones back on top. We certainly got our money’s worth from that show in the Garden, which was later documented in the Stone’s “Get Yer Ya Yas Out” live album. British blues rocker Terry Reid, who I had seen at Eagles in Seattle, opened. He was followed by B.B. King and his big band. Then the Ike and Tina Turner Revue came on and set the stage on fire. The Stones’ set was great. Mick Jagger was a whirling dervish. Keith Richards showed his new love of open-G tuning, and I was reminded all over again why Charlie Watts was my favorite Stone and the group’s most valuable player. The band’s new guitarist, Mick Taylor, showed himself to be a lyrical soloist and a great partner for Richards.

Playing a New Year's Eve showcase in Central Park with the Sting Rays (photo by Jeff Fereday)

Me, Mark Wenner, and Jeff Fereday

There were some fine harmonica players at Columbia when I went there. Mark Wenner made a big impression on me, not only with his harp playing but with his loud, stylish arrivals on the Morningside Heights campus bestride a huge Harley. Mark later went on to found The Nighthawks, one of the Northeast's most celebrated blues bands. This is Mark with me and another Columbia pal, Jeff Fereday. Mark is trying to get us to sing the Columbia fight song "Roar, Lion, Roar” and it's not working.

Dave Waldman

The best of the harmonica players at Columbia was Dave Waldman, who later moved to Chicago and became one of the finest blues harpists on the planet. (He also plays a mean guitar, piano, mandolin, and fiddle.) Dave was a big inspiration for me in my early days as a player. It was Dave who introduced me to Paul Oscher, who unlocked at least a few of the many mysteries about the harmonica for me.

Me and Paul Oscher

Paul Oscher had recently left Muddy Waters' band and moved back to his native Brooklyn when I arrived in New York City. Dave Waldman was taking lessons from Paul and he told me that I would be crazy not to get some tips from Paul. After some persistence, I did manage to get a few lessons from Oscher. He showed me the tongue-blocking technique that is the key to a deep blues harp sound and walked me through what was really going on in Little Walter's "Juke." Hearing Paul's beautiful tone and faithful Chicago sound, inches away and purely acoustic, without echo or other effects, was the biggest revelation I've ever had as a harp player, and it saved me years of grief. I caught many of Paul's gigs around the city and learned from him more than I can ever describe about not just harmonica playing but the blues itself. Waldman was right--I was insanely lucky to been exposed to Paul when I was just starting out as a player. Paul is more active than ever today. He is a true triple threat, having mastered blues harp, guitar, and piano. There is no deeper bluesman in the business today.

Walter Horton

There was great music somewhere in New York City every night of the week, but it wasn’t a strong blues town. Boston, on the other hand, had a long tradition of hosting the world’s best blues talent. During my college days the best blues club in Boston was Joe’s Place in Inman Square. The first time I went there, I was dumbstruck. All the walls were lined with huge prints of the great blues artists onstage at the club, the waitresses all wore T-shirts that said “Nobody Has The Blues Like Joe’s,” and the club booked blues artists that never seemed to play in New York. The venue of my dreams, for sure. I started hitchhiking up to Boston to catch the shows at Joe’s. I saw Otis Rush for the first time there. Big Walter Horton played there pretty regularly with John Nicholas and I tried to get up to Boston for his shows. Eventually I was familiar enough to him and had bought him enough shots of Seagram’s VO that he invited me to share his booth between shows. Walter as a person was a fascinating combination of shyness and deep intensity. He was a great bullshit artist. The yarn that got me the most excited was when I asked if I could look him up for a harmonica lesson if I was ever in Chicago. He wrote down his address on Wentworth Street for me, looked at me conspiratorially, lowered his voice, and said “If you come see me, I’ll show you everything I know. Cost you $20, but it’ll be worth it, because I got a motherfuckin’ x-ray machine at home and I’ll slap my face right up against it when I blow and you’ll see EVERYTHING.”

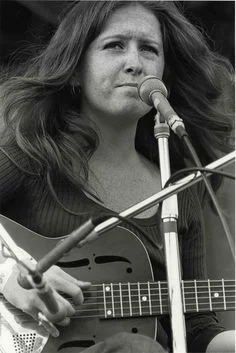

Bonnie Raitt

The Sting Rays made a foray one day to the thrift stores on Third Avenue on the East Side to look for some cheap stage clothes, and we noticed a sign in the window of a club announcing that Mississippi Fred McDowell was playing a late show that evening. We showed up early, around eight, paid our $5 cover, and nursed beers for a couple of hours until Fred’s opening act, a young woman from Boston named Bonnie Raitt, showed up and launched into her set. Raitt’s first record had not yet been released and none of us had heard of her. Bonnie explained after a few songs that she had arrived after opening an earlier show with McDowell at the Bitter End in the Village, and that the plan was for Fred to head uptown to join us after he finished his set there. About a half an hour later, Raitt was openly musing about whether Fred would actually make it: “I sure hope that Fred makes it. He was, well, feeling no pain when I left.”

We had been there for hours with no Fred McDowell. My bandmate Bob Ahrens stood up in disgust and announced, “That’s it. I want my five dollars back.”

In about three seconds there were three large Italian gentlemen surrounding our table. One of them immediately got into Bob’s face.

“Oh, ya want your money back, do you?” he growled. “The show wasn’t good enough for five bucks, eh?”

He strode over to the door of the club, wrenched the door open and held it there while simultaneously reaching into his pocket and pulling out a five dollar bill. He waved it in the air and then threw it out onto the sidewalk.

“There you go, buddy,’ he sneered. “There’s your precious five dollars. Now get the fuck out of my club!”

About a block down the street Bob pulled a very nice framed photograph of Howlin’ Wolf out of his leather jacket. Bob had lifted it off the wall in the club on his way out the door. Bob was a huge Howlin’ Wolf fan, and he hung that photograph in his apartment for years. One night there was a crash in the living room and when Bob went to investigate the shattered photo of the Wolf was lying on the floor. Bob learned later that Howlin’ Wolf had died that night. When it came to the Wolf, it was easy to believe in the supernatural.

Howlin’ Wolf

I was lucky enough to see Howlin’ Wolf perform many times when I first lived on the East Coast. My first experience with the Wolf was seeing him open for John Lee Hooker on a show at Hunter College in New York City in 1970. The Wolf, perhaps aroused at not being the headliner, came out in full force for his first number, “They Call Me the Wolf.” He roared. He howled, He shook his vocal mike in front of his crotch. He got down on his knees and pounded his fists on the stage. When he was through wringing every ounce of feeling out of that opening tune, he seemed spent. His sax player Eddie Shaw ushered him to a chair onstage, and the Wolf did the rest of the show from that perch. But once you saw and heard what only the Wolf could do, he had you. I remember him at another show making “Going Down Slow” into an incredible piece of drama—the Wolf was a world-class actor—as he looked out as us mournfully as if he was sure it would be the last time.

I hitchhiked up to Boston to catch a show at Joe’s Place right after Paul Oscher had showed me tongue blocking on the harmonica in that music store in Brooklyn. As usual, I stopped on the way to spend the night with friends who were going to Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. I spotted a poster next to a dormitory elevator advertising a Howlin’ Wolf show that night at Sir Morgan’s Cove. All of my friends begged off due to pathetic excuses about papers to write and upcoming exams, so I walked across town alone to see the show. It was a weeknight, an off-night calendar filler for Wolf and the band, and the crowd was small. The Wolf played the harmonica on some of his records and would pull out a Marine Band for a couple of songs each gig, but this night the Wolf was in full harmonica mode, blowing harp the entire set. The Wolf played harmonica just the way he sang—with a huge sound. I had tongue blocking on the brain, and I just had to ask the Wolf if that was part of his secret, too.

The Wolf finished his first set and the band hit the bar. But Wolf stayed right where he was, on a stool under the lights, staring balefully at his feet. This was my chance, and I got up and approached him.

How am I supposed to address him? What do I call him? “Mr. Wolf”? “Mr. Burnett”?

I planted myself in front of him. He was the biggest man I’d ever seen in my life. His bowed head was huge. I started stammering out my story, sounding like a complete idiot—I was a harp player, I knew Paul Oscher, he was playing such beautiful harp tonight, Oscher had shown me tongue blocking, and I just wanted to know if he used that approach, too.

When I started speaking to him, Wolf slowly raised his gaze from my feet to my knees to my waist to my chest and finally to my face. And then, for about fifteen seconds that seemed like a million years, he locked eyes with me. I was one second away from turning and running when he finally spoke.

“The Wolf don’t tell anybody his tricks,” he growled firmly. “If you find out, the Wolf don’t mind. But the Wolf ain’t gonna tell you about it.”

Phil Schaap on the Columbia campus

In the Columbia neighborhood of Morningside Heights my classmate Phil Schaap somehow convinced the local bar, the West End Café on Br0adway, to turn its back room into a swing jazz venue (this made no sense on any level, but is a testament to Phil’s persistence and powers of persuasion) and for a few years there was great jazz going down there most nights. The legendary guitarist Tiny Grimes and equally renowned pianist Sammy Price each had a regular weekly gig there. Price's band included Papa Jo Jones, Count Basie's original drummer and my all-time favorite percussionist. Hearing Jones play a shuffle with brushes was an unforgettable experience. Jo was quite a character and would occasionally go off script and liven up the musical proceedings by interjecting a spontaneous oration. I remember one night when Sammy Price was introducing the band. When he got to Jo, the drummer stood up from behind his drum kit and announced to the room of college-age beer drinkers that he had some very important information to impart to us.

“Young ladies and young gentlemen,” he intoned. “I have many life lessons to impart to you, because I have had a very, very rich life and I have seen many, many things. I have met the crowned heads of Europe. And I have met them not only in their official capacities, ladies and gentlemen, but I have also seen many of these royal characters crawling on their hands and knees in the finest whorehouses on the continent…” Price sighed and stared down at his keyboard, waiting for Jo’s history lesson to run its course.

Phil also took an interest in the Sting Rays and financed a 45 rpm single we released featuring a couple of original tunes. Phil also began hosting a jazz radio show in 1970 on WCKR, the Columbia campus radio station that reached the entire New York metropolitan area. Phil hosted that program for decades. He has taught jazz at Columbia, Rutgers, Princeton and Juilliard. Phil had a long career producing, remastering, and writing for a long string of jazz reissues, for which he was nominated for eleven Grammy awards—he took home seven of them. Now he is the Curator of Jazz at Lincoln Center. Woody Allen modeled his character in his “Sweet and Lowdown” movie after Phil. A truly amazing guy.

Early in 1971 the Sting Rays went down to Ungano’s on W. 70th Street to catch Ry Cooder. We had learned about him from his work with the Stones, and he was on the road promoting his first solo album. It turned out that on this show Cooder was the opening act—Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band was the headliner. I had some sense that Beefheart was an unusual talent from California, but I had never heard his music. Cooder played a killer set that night with a bassist and drummer. Hearing his patented approach to slide guitar in person was a revelation, and hearing him play blues mandolin set me on a path toward the music of his inspiration, Yank Rachell.

After Cooder’s set, a strange crew began to assemble on the small stage. One guy wore a baseball cap, pajamas, and a bathrobe. The drummer sported a pair of cheesey wraparound shades. Another character had a soul patch spot of a beard under a felt top hat and carried a soprano sax. I learned later that this was the classic early Magic Band with Zoot Horn Rollo, Mascara Snake, Rockette Morton, and Drumbo, but that night they seemed at first glance to be thrift store refugees from Weird Town. The players took their positions, and the guy in the felt hat, who we figured had to be Beefheart because he exuded band-leader-type strength, placed the bell of his soprano right on top of the vocal mic and gave a brief glance to the drummer. Then there was an explosion.

The first “song” seemed like a full-on sonic assault. The musicians weren’t so much playing but drilling completely different rhythms and sounds, Beefheart’s top-volume soprano sax work sounded something like a dying animal, and there was nothing even approximating a groove to hold any of the wild pieces together. It took me about a minute to decide that these clowns were sick poseurs who had no clue how to play and were just slinging out the weirdest shit that they could summon, and I began thinking about how much of this I would be able to stand.

Suddenly Beefheart and the entire band shifted instantaneously as a unit into a completely different rhythmic cacophony and we all realized that these guys all knew EXACTLY what they were doing and this was not complete madness but total method. I’ve never had anything like that experience listening to another band—where my perception of the music and the players flipped completely in an instant.

Then Beefheart started singing, and that set off another mental hand grenade for us because this was clearly a guy who had cut his vocal teeth on the Howlin’ Wolf records that we all loved. The leader of this bizarre gang turned out to be a blistering, no-holds-barred blues singer. Say what you would about the Captain and his boys—you would never forget them or confuse them with someone else.

After seeing that show we all started listening to “Trout Mask Replica,” Beefheart’s magnum opus double album. That man was really something. Here’s some audio from that Ungano’s show:

I had another memorable night at Ungano’s just two months later when my friend Jon Jacobson and I went to see Taj Mahal there. Seeing shows at clubs in New York City (Ungano’s seated about 250 people) could be frustrating in terms of getting a decent sight line to the stage, so Jon and I were thrilled when we were given a small table in a section that was on a raised platform where we had a great view of Taj and his outstanding guitarist Jesse Ed Davis as they kicked into their set. But after a few tunes a waiter came up and asked us to move our table back a couple of feet, which gave him just enough room to cram another small table right in front of us. Damn, I thought, so much for finally getting a great seat.

A minute later the waiter escorted a man and his date to the table, placing an unopened bottle of Jack Daniels and two glasses in front of them. The newcomer turned his profile to us as he talked to his date and we realized that it was Jimi Hendrix who was sitting two feet away from us. During the rest of the show Hendrix divided his attention pretty equally between paying attention to his lady friend and watching Jesse Ed Davis’ guitar playing. At one point I went to the restroom and when I came back to my seat I had to walk past Hendrix. I had a sudden inspiration to stop and ask him “Excuse me, but didn’t you go to Garfield High School (Hendrix’s Seattle alma mater)?” but as I approached him Jimi shot me one of those glances and I chickened out.

One of the coolest and most unique experiences I had while I was in New York City was a blues piano festival put on by an unlikely venue, Kenny’s Castaways on E. 84th Street.

They kicked it off with a week-long gig featuring the legendary Roosevelt Sykes. Sykes developed his barrelhouse piano style playing for the men who worked in the turpentine camps in the deep South. His first record, recorded in 1929, was “44 Blues,” which was a huge hit with a unique feel that quickly became a blues standard. He also wrote “Drivin’ Wheel,” which Junior Parker turned into a huge hit in the 1960s, and “The Honeydripper,” which has been covered by a small army of artists. Sykes was a born entertainer with a sweet smile, an appealing voice, a great left hand for boogie woogie, and a ton of great risqué material. I could have listened to him for hours.

The follow-up keyboard wizard booked into Kenny’s, Little Brother Montgomery, was just as remarkable. He and Sykes were the same age, but Montgomery seemed like a player from an earlier era. Little Brother was from New Orleans, and his blues, which were more intimate and subtle than Sykes’, reflected the influence of early jazz and ragtime in the Crescent City. Listening to Little Brother Montgomery, sitting twenty feet from his keyboard in a small, hushed club, you felt that you were in the presence of a living link to the very beginnings of the blues and jazz.

The last pianist booked for the festival was someone with a strange stage name I had never heard of, but Sykes and Montgomery had been so fabulous that I didn’t want to run the risk of missing something equally amazing, and I was there early. I ordered a drink and watched a thin black man in a jean jacket and a fur cap warm up at the piano while a Fender bass player and a conga player set up behind him. A few minutes later the emcee announced “the amazing Professor Longhair, all the way from New Orleans,” and then the fun started: a piano style that was completely different from anything I had ever heard. Longhair was pounding out his trademark blend of boogie woogie, rhythm and blues, calypso, and flamenco music and singing in a wild, croak of a voice. It was the coolest, funkiest stuff I had ever heard. Hearing Professor Longhair’s musical stew for the first time live in close quarters was a truly unforgettable experience.

Professor Longhair

New York City has never been a mecca for country music, but country acts did come through the Big Apple. I finally saw Merle Haggard in person for the first time in 1970 when he played the Felt Forum in Madison Square Garden. Merle closed the show with the obligatory “Okie From Muskogee,” but up until that finale he and his fabulous band, The Strangers, brilliantly covered the best of the subgenres of country music—western swing, country blues, hardcore honky tonk, Dixieland—as well as Merle’s already impressive list of hit songs. Merle was also still including a segment in his show in which he did phenomenal imitations of many country stars with widely different vocal approaches, including Hank Snow, Charlie Pride, Johnny Cash, and Buck Owens. I left the Garden absolutely convinced that Merle Haggard was the most musical singer in the history of country music.

In January of 1973 a New Jersey radio station switched to a country-music format and rented out Max’s Kansas City to host showcase for big country stars to promote their programming change. It was an interesting choice of venue because in those days Max’s was the favorite hangout of Andy Warhol and the New York City art crowd and a home of sorts to bands like the Velvet Underground. One of the first country acts to perform at Max’s was Waylon Jennings, whose career had just started to gain big-time momentum thanks to his “Honky Tonk Heroes” and the “outlaw” music pioneered by him and Waylon Jennings.

Waylon brought an insanely great band into Max’s that night. Ralph Mooney, one of the greatest pedal steel players ever, was on the bandstand, and the rhythm section was outstanding. The huge bonus and revelation for me that night was that the two players who were out front and center were Waylon and a brilliant harmonica player named Donnie Brooks. Years later I got to know Donnie and would learn about his blues roots in his hometown of Dallas and his years in the New York City folk scene. All I knew that night was that this guy was a monster player and was really driving the band. The band kicked off the show with a couple of instrumentals and then Waylon strode onto the stage, looking like he had just woke up from a backstage nap. Some woman with a New York accent called out “Who the hell are you?” As if this was planned as a killer kickoff for the show, Waylon peered into the lights and took the mic. “I’m Waylon fucking Jennings, ma’am,” he barked just before hitting the downbeat of his first tune. Waylon had it all—the voice, the tunes, the band, and miles of charisma. That show also gave me an understanding of how much his guitar playing meant to his unique sound.

Video of D0nnie Brooks with Waylon Jennings

Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris

I caught another memorable, but far less inspiring, country show at Max’s Kansas City in March 0f 1973 when Gram Parsons came through New York City to play there. I talked up Parsons’ show for weeks to my city friends, very few of whom had any interest in or affinity for country music. “If you ever to go see one country show, this is the one” was my rap to them. I ended up shepherding several folks down to Max’s, which was near Gramercy Park. Our trip started promisingly as we spotted a large Silver Eagle bus with “Gram Parsons, Reprise Recording Artist” emblazoned on the side. We walked up the steps to the club and commandeered a couple of tables. Gram and his band members showed up and began messing with their equipment and tuning their guitars.

At some point the rushed sound check turned into the show; Gram and the Fallen Angels had a very casual approach to showmanship. The band was not a cohesive or particularly talented outfit; The steel player was pretty good, but the rhythm section was a mess. The Fallen Angels were obviously under-rehearsed. There was little or no patter to the audience between shows. Parsons sang fairly well, but he looked very pale and bloated and his hands were trembling. This was Emmylou Harris’ first tour. She sang spot-on harmonies and played tambourine with a wide-eyed look on her face. Parsons’ had a solid command of country and folk styles, but he couldn’t effectively deliver a rock and roll tune, and the Fallen Angels did a lot of moldy rock tunes that night—questionable numbers like ”Bonie Maronie” that they had no affinity for. The show was devolving quickly. It was hard to process how someone so talented as Parsons could show up for a New York showcase gig with an embarrassing band and what can only be described as a “who gives a damn” attitude.

Parsons suddenly announced that Dave Mason from Traffic was going to come up and join the band for a couple of tunes. A very drunk Mason got up from a nearby table and stumbled over to the stage. He was handed a guitar, strummed a chord, and broke a string. There was no extra guitar, so the stumbling show came to a complete halt for a few minutes to change a string. I avoided the glances from my friends. In an attempt to keep the show going, Gram and Emmylou finally stepped up to the mics and did an unbelievably gorgeous rendition of the Louvin Brothers’ “Satans Jewelled Crown.” Their voices blended perfectly and it was a magic musical moment. Then the band reconvened with Mason, there were a few more disorganized tunes, and we headed back uptown. Years later a live album was released that was recorded at a radio station the day after I saw the Fallen Angels. It’s not a brilliant record or anything, but Parsons and the band sound far better than they did at Max’s.

Otis Redding

I was in college when I discovered another huge musical influence: Otis Redding. I wore out three copies of his album “Otis Blue” before I graduated, and his “Live In Europe” LP was in really heavy rotation, too. The initial attraction, of course, was Otis’ incredibly passionate voice and performance style. “Mr. Pitifiul” had that heartache in his singing that all great soul singers have, and he was all sex, all the time, in a really joyful way. As I got deeper and deeper into Otis, I began listening more and more to what Booker T and the MGs were doing behind him on those records. Every guy in that band—Booker on keys, Duck Dunn on bass, Steve Cropper on guitar, and the amazing Al Jackson, Jr. on drums—was a star. Otis’ records with them had a very distinctive style, but somehow their arrangements were always fresh, surprising, and soulful as hell. Like the best blues, they came up with infinite variations on the same approach and left tons of holes for Otis’ voice. No other band could have ever come up with the arrangement that they devised for “Try A Little Tenderness.” Otis’ Stax albums gave me a whole new way to think about how to use a band.

And, like Paul Butterfield and Gram Parsons, Otis Redding turned out to be a gateway drug for me, and I am still discovering the endless catalog of stellar soul singers and recordings: Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, Aretha Franklin, James Brown, Little Willie John, Solomon Burke, Don Covay, Wilson Pickett, Arthur Alexander, James Carr, William Bell, Sam and Dave, ZZ Hill, Al Green, Dan Penn. The list of great soul artists, especially from the ‘50s through the ‘70s, just seems to go on and on, and I have spent thousands of hours listening to their music.

Soul, naturally, led back to black gospel and some of the greatest voices ever recorded. As far as the men are concerned, my big favorites are Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers, Clarence Fountain and the Five Blind Boys, Ira Tucker and the Dixie Hummingbirds, and Claude Jeter and the Swan Silvertones. The female gospel artists that move me the most are Marion Williams and the irrepressible Dorothy Love Coates.

One night in 1973 some friends and I trooped downtown (to Hunter College, I think) to see a Jimmy Reed show. Jimmy was notorious for being a no-show, and sure enough after waiting for an hour past the advertised starting time, a nervous hippie emcee came out and told us that Jimmy couldn’t make it “due to illness.” He quickly explained that tickets would be refunded, but that we should stick around because they had lined up a great fill-in act, the Dixie Hummingbirds. The audience—including me—wasn’t hip to them, but Paul Simon’s “Love Me Like A Rock”—on which the Hummingbirds sing backup—was a big hit then and Ira and the guys strode out on stage and quickly launched into their version of Simon’s tune, immediately grabbing the disappointed ticket holders. Those of us who stayed in our seats treated to a truly incredible gospel set featuring the legendary Ira Tucker on lead, William Bobo on bass, and the great Howard Carroll on guitar. Unforgettable.

Video of Howard Carroll with the Dixie Hummingbirds

I stayed in New York for a year after somehow managing to graduate from Columbia. The Sting Rays were still popular in the Morningside Heights neighborhoods, but our record hadn't led to any opportunities. We played some interesting shows, including a big New Year’s Eve showcase in Central Park and a Richard Nixon counter-inaugural broadcast on WBAI. After five years in the big city and with the band not doing much, I made the hard call to pull up stakes and move back to Seattle.